|

| My patient was also a marionette. |

Another way to put it - after reading the paper, I'm not sure what was treated, and whether it (whatever it was) required treatment.

Also, I'm not clear on what the outcome of treatment was.

Can Nebulized Naloxone Be Used Safely and Effectively by Emergency Medical Services for Suspected Opioid Overdose? is a retrospective study of the use of nebulized naloxone by EMS in Chicago. The methodology is, as usual, important to understanding the conclusions.

Methods:

The Chicago FD EMS system had already implemented the use of nebulized naloxone (2mg in 3ml NS) for various indications, excluding patients in shock or who were apneic. The researchers reviewed the EMS patient care reports of any patient who was given nebulized naloxone for any reason, including "suspected opioid overdose, altered mental status, or depressed respirations."

That's the first item that bears some scrutiny - these indications are vague, and reflect some different conditions. Some of these conditions require naloxone, others don't.

Do all patients with suspected opioid overdose require naloxone? Probably not.

For that matter, do all patients with altered mental status require naloxone? Likely no.

Respiratory depression, of course, is a very good reason to give naloxone, but no definition is provided; Respiratory rate? Hypoxia? Hypercarbia?

Next, what was the outcome they were studying?

The researchers looked at the PCRs to determine if the response was "complete, partial, or no improvement." This is an unfortunate choice of an outcome measure, for two reasons.

The first is that it begs the question - what was the desired response? Are we aiming for clarity of speech, or resolution of hypoxia, or reversal of miosis?

|

| Mission accomplished. |

Results:

When we look at the results, we can't be sure what to make of them, given the study design. Out of 105 patients, naloxone was given to:

Suspected opioid overdose 70 patients (66.7%);

Altered mental status 34 patients (32.3%);

Respiratory depression 1 patient (0.9%).

This is an odd collection of diagnoses, as only the last item is viewed by toxicologists as an indication for naloxone. "Suspected opioid OD" can be confirmed through urine, serum, or just asking the patient later - it isn't a diagnosis that in itself requires treatment.

"Altered mental status" may be due to the use of opioids, but it may also be coincidental. For example, Peter Canning describes a case in which he gave naloxone to a patient who had a subsequent return to full LOC. It turned out to be entirely coincidental - the patient actually had an intracranial hemorrhage.

|

http://xkcd.com/552/ |

Complete response 22%

Partial response 59%

No response 19%

This is the frustrating part - they don't say what the responses were (Increased RR? Wide pupils? Screaming and vomiting?). Also frustrating is that the majority of response were partial, which can be really subjective. They try to break down the results in the table:

...which doesn't really show any meaningful differences between the complete/partial/none-responders.

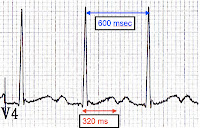

In fact, it shows an interesting similarity that all 3 groups have: the average RR was above 12/minute. In many patients, it appears to have been significantly higher- the "No Response" group had an average initial RR of 18.

The bible of toxicology describes the goal of naloxone administration as restoring "adequate spontaneous ventilation," not the reversal of slurred speech, sleepiness, or tiny pupils. Frankly, it's also not a medical goal to thwart someone's high. Nonetheless, at least one toxicologist feels that nebulized naloxone is an "attractive alternative."

My take on this study:

You can nebulize anything, and it was shown here that paramedics could nebulize a clear liquid containing salt and naloxone.

It didn't show us if it worked, because almost 80% of the responses were "partial" or less.

Even with a 22% rate of "complete" response, we don't know what to conclude as they didn't show us what they were trying to treat.

Review of the protocols:

Naloxone is only mentioned in the altered mental status guideline - there is no indication under the "Overdose/Poisoning" or "Respiratory Arrest" sections.

You generally don't want to reverse opioids unless you find coexisting respiratory insufficiency. Not a whole lot of benefit, and enough potential for adverse effects!

For example...

Enjoy!