At the outset, let me emphasize that the Sponsor Hospital Council guidelines suggest that morphine be used, up to 0.1 mg/kg IV, if chest pain of suspected cardiac origin is not relieved with 3 tabs/sprays of nitroglycerin. That hasn't changed!

The benefit of morphine in ACS

Angina and infarction hurt, and morphine can treat that. There are other supposed benefits (reducing ischemia, reducing "stress," blood pressure reduction), but these are mostly theoretical, and often can be accomplished with other agents.

|

| For example! (Source) |

The risk of morphine in ACS

Of course, morphine causes (infrequently) respiratory depression, hypotension, or depressed mental status. These are true for any patient, not just those with ACS, and are generally avoidable with careful administration.

The patient with ACS may face specific risks with morphine though, leading to worse outcomes with their ischemia. This is a controversial area, and there is little good evidence. Nonetheless, breathless headlines like this came out after publication of a study in 2005 (PDF link).

|

| "News" link |

1. Does morphine directly harm the myocardium in ACS?

Some people are concerned that morphine, during an episode of ACS, may directly harm the ischemic heart. The authors of the "morphine increases death risk" study remark on the discussion section that "in animal studies, morphine has been demonstrated quite conclusively to actually increase myocardial infarction size."

They cite, as "quite conclusive," a study from 1982, where rats where given a subcutaneous dose of morphine at 3 mg/kg. (That would be 210 mg for an adult human!) They then performed open-heart surgery, and tied-off a coronary artery - just blocked it off. When they looked at the hearts 2 days later, the rats who had morphine had MIs that involved 10% more myocardium than the morphine-free rats.

|

| Rat open-heart surgery, w/ ligation of LAD. source |

On the other hand, North Carolina researchers studied rats who underwent a limited period of coronary occlusion, and found that the morphine pre-treated rats had smaller infarct extent.

So it's an open question whether any of these animal studies represent great (or even mediocre) evidence that can guide our clinical management. It's not conclusive, that much is clear.

2. Do the adverse effects of morphine (hypotension, hypoxia) cause harm in ACS?

Perhaps morphine doesn't have a direct toxic effect on the myocardium, but the known adverse effects can certainly cause problems. Generally, though, these are not common if morphine is administered cautiously, and in practice hypotension or hypoxia are rare.

One study that has been cited as demonstrating the potential for hypotension in MI patients was conducted 1969. In The effect of morphine on blood pressure and cardiac output in patients with AMI the authors gave 15 mg morphine, intramuscularly, to 10 patients with an MI. They found a "slight tendency to development of orthostatic hypotension."

So if you give 15 mg IM of morphine, you might want to be ready to give them some fluids, or just not have them stand, but this doesn't seem persuasive as a severe adverse effect.

3. Does morphine "mask" the ischemic pain, rather than treat it?

This is really the most interesting question - should we avoid using opiod medications that could "mask" recurrent or continuing ischemic pain, so that we can make better decisions about further interventions? I.e., does morphine delay angiography?

Spoiler alert: We have no idea. There is no evidence here, only opinion.

Chest pain today = abdominal pain 50 years ago?

An analogy with abdominal pain is appealing. In the past physicians relied on the severity and evolution of abdominal pain to aid them in the decision to pursue surgery. If a patient's pain was "masked," the physicians had few means to understand the evolution of the disease. Nowadays, given the accuracy of blood tests and CT scans, most clinicians feel they may safely treat the abdominal pain prior to full evaluation of the patient.

A number of people would argue that we are still at the "pre-CT scan" point now for ACS. The argument is that, absent angiography, we have few means to establish the need for invasive treatment. Like the surgeons of ye olden days, we may be led to a "false sense of security" after morphine reduces the pain.

This is an important question since, in the UA/ACS patient, we use "recurrent ischemic pain" as one factor determining how urgently the patient is taken to angiography. Dr. Stephan Smith, of Dr. Smiths ECG Blog points out one case, for example, where he believes that the heavy-handed use of opiods contributed to a delay in angiography.

But how much do we depend on the character or presence of recurrent/refractory pain, as opposed to other factors? We have the ability to check troponins, perform sequential (or even continuous) ECGs, and we can look "directly" at the myocardium with a bedside echo. We are not dependent on the unimpaired report of symptoms - technology has provided a few tools!

Two patients

Let's consider two extremes, two different patient presentations.

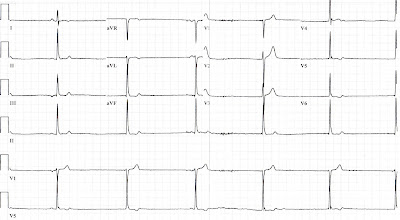

First, how should we consider a patient who adamantly denies any chest pain/pressure (or back pain, shoulder aches, or jaw discomfort...), but has an ECG that looks like this:

|

| True story. Yeah, it was an RCA. |

Second, how should we proceed with a patient who describes "crushing" chest pain, with left arm radiation, an sensation of doom, etc., and looks like this...

... but whose ECG looks like this?

|

| Stop looking, it's normal. |

In the end, it's worth pointing out that Dr Smith's "missed MI" had an initial ECG that actually showed a STEMI, albeit an uncommon (but not rare) pattern.

Bottom line: Still a recommended therapy!

This post contains more opinion than I usually like to write. There just isn't the level of evidence to help us. I think my observations are pretty mainstream, however. Talking with my colleagues, most of them tend to agree with the use of morphine in this situation. One emergency physician remarked "That's what morphine is for - to mask pain."

Despite the hypothesis-generating evidence provide by the CRUSADE trial, there is little other evidence that suggests that morphine is harmful, or that analgesia must be deferred while patients are in pain. Despite the inflammatory press coverage of the CRUSADE results, the AHA continues to recommend the use of morphine in ACS.

But hold the bourbon!